Scaffold protein h1 code#

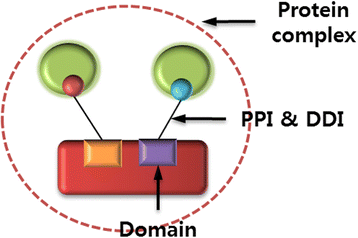

Methods include cysteine bioconjugation 31, 32, protein semisynthesis, such as native chemical ligation 33, 34, expressed protein ligation 35 or sortase-mediated ligation 36, as well as genetic code expansion 37, 38. The combination of chemical methods to modify histones together with mass spectrometry (MS) has been proven powerful in identifying the relevant writers, readers, and erasers for specific (core) histone-PTMs 15, 26, 27, 28, as chemical protein synthesis allows for the generation of histones of defined, homogeneous modification states 15, 29, 30. Furthermore, ubiquitylation of H1 was linked to activation of gene expression 22 and antiviral protection 23, and more recently H1 ubiquitylation has also been put forward as a histone mark relevant in the response to DNA damage 24, 25. Yet, there is growing evidence that linker histone H1 regulates cellular functions by direct protein-protein interactions 18, 19, 20, 21. In particular, the long, highly unstructured and lysine-rich CTD is prone to degradation and yields insoluble and truncated proteins 17. Moreover, intrinsic characteristics have even hindered in vitro analyses of modified H1 following recombinant expression. Yet, although H1 is closely linked to the regulation of DNA structure and dynamics 1, 3, 4, 5, a lack of appropriate technologies, in particular the absence of site-specific and modification-specific antibodies, has handicapped research on H1 and has significantly hampered our ability to decipher its contribution to the histone code. Unlike the core histones, H1 binds dynamically to chromosomes and plays a fundamental role in the formation of higher-order chromatin. While the functional relevance of specific histone marks is increasingly well understood for core histones, this is not the case for linker histone H1. Histones are intensely post-translationally modified resulting in a complex chemical language, the histone code, which is interpreted by specific protein complexes and enzymes to mediate transcriptional responses and downstream functions 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. Recent studies indicate that LLPS plays a role in chromatin maintenance and chromatin organization, even though the extent to which these processes are affected by LLPS in cells requires further investigations 7, 8, 9, 10. Biomolecular condensate formation by liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) leads to local enrichment of proteins and is increasingly recognized as a general mechanism of how cells can organize biochemical reactions in time and space 6, 7. They consist of a central structured and highly conserved globular domain (GD, 70–80 amino acids) flanked by unstructured N-terminal (N-terminal domain, NTD ~40 amino acids) and C-terminal (C-terminal domain, CTD ~100 amino acids) tails, which exhibit significant sequence divergence within the same species 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Linker histones of higher eukaryotes have a tripartite structure. The subtypes H1.1 to H1.5 and H1x are ubiquitously expressed in almost every cell type, with H1.2 and H1.4 being the predominant variants in most human cells. Human cells contain eleven variants of linker histone H1, including seven somatic subtypes (H1.1 to H1.5, H1.0, and H1x). Thereby, the small basic protein stabilizes the nucleosomes and provides the structural and functional flexibility of chromatin. The linker histone H1 additionally binds at the nucleosome entry and exit sites in a dynamic manner to form higher-order chromatin structures. Nucleosomes form the basic repeating structural units of chromatin and consist of DNA wrapped around an octamer of the four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). In eukaryotic cells, genetic information is tightly packaged and organized in a nucleoprotein complex termed chromatin.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)